Our music charity Child’s Play India Foundation is fifteen this year, a milestone we have been celebrating with a slew of concerts, workshops and music camps since this year began.

It gives us singular pleasure to host the Goa debut concert at the Maquinez Palace Auditorium 1 Panjim on 27 April 2024 (donation passes at Furtados Music store and also at the door before the concert) of an exceptionally gifted child from Mumbai, Ayaan Deshpande.

Born on 27th December 2013 in Tokyo and raised in Mumbai, Ayaan has been studying the piano at the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI) Music Academy, National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) since May 2021 under the guidance of Ms Aida Bisengalieva.

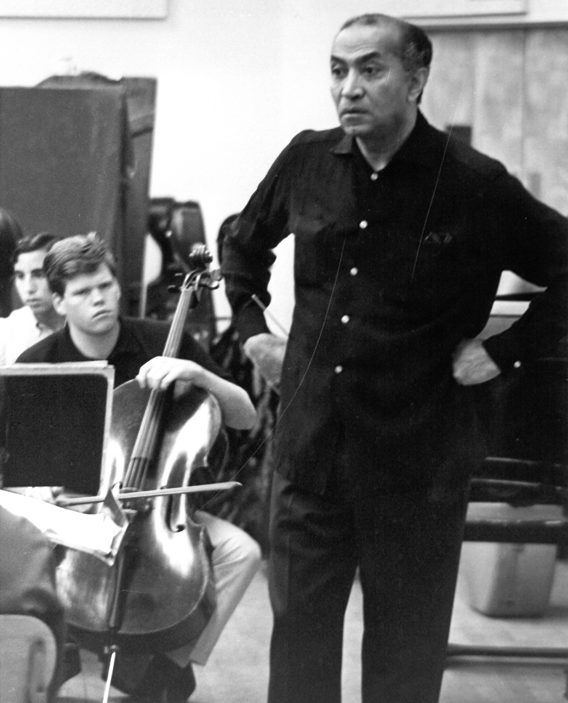

Six months later, in November 2021, at just seven years of age, Ayaan gave his first public performance with the SOI Chamber Orchestra under the direction of maestro Marat Bisengaliev at the Tata Theatre, NCPA.

Along with playing the piano, Ayaan also loves to compose. He has composed a Sonata, a Waltz, a Nocturne, a piano & strings Quintet as well as a few other pieces. Ayaan’s Goa recital will also feature his own three-movement piano sonata. I can’t wait to hear its Goan premiere!

In July 2022, Ayaan gave his debut piano recital on the Jamshed Bhabha Theatre stage performing the works of Mozart, Chopin, Debussy along with one of his own compositions.

Ayaan has also performed on various occasions at the Little Theatre NCPA, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, (CSMVS) Mumbai, Tata Theatre NCPA, Happy Home & School for the blind – Worli, Prithvi Theatre, Mazda Hall – Pune.

In May 2023, he gave his first international concerts at Kurmangazy Orkestri Kazakh Concert Hall in Almaty, Kazakhstan, performing a solo piano program, duets accompanying violinist Marat Bisengaliev, as well as performing with an orchestra of Kazakh folk instruments. He also performed at the School for Autistic Children and at the Republican Kazakh Music School named after renowned Kazakh conductor, composer and musicologist Akhmet Zhubanov (1906-1968).

Ayaan was selected as a winner at the Golden Key Music Festival of Vienna, 2023 in both piano performance and composition categories. He performed during the festival at Palais Ehrbar and the Bӧsendorfer Hall in Mozarthaus.

Ayaan performed at the Mumbai Piano Day in September 2023 playing a program of Jazz and Western classical music. On 31st October and 1st November 2023, Ayaan performed Haydn Piano Concerto No 11 with the SOI Chamber Orchestra conducted by maestro Marat Bisengaliev in Mumbai and Delhi.

In 2023, Ayaan was featured among the Unstoppable 21 talented youngsters by the Times of India, India’s leading English newspaper.

I was reading up on the concert hall Ayaan performed in last year, the Bӧsendorfer Hall in Mozarthaus Vienna. The Mozarthaus was the residence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) from 1784 to 1787.

It is hallowed ground as it is where the genius composer wrote so many of his masterpieces, notably his operas, Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro, 1786) Don Giovanni (1787), 12 of his 27 piano concertos among so many others. What a rare honour and privilege to actually perform in such a space!

In fact, Ayaan performed one of those piano concertos (no. 21 in C major, nicknamed ‘Elvira Madigan’, K. 467, completed in 1785) just last Sunday in Mumbai with the SOI Chamber Orchestra to a thunderous ovation. He played his own composed cadenzas.

Mozart also features on Ayaan’s concert programme, a work from a little earlier, 1778, his Piano Sonata in A minor, K. 310.

Out of Mozart’s 18 numbered piano sonatas, only two are in a minor key, the other being the Piano Sonata no. 14 in C minor, K. 457.

Mozart’s compositions are not often in a minor key. Out of his more than 600 completed works, a mere 30 are in a minor key. Apart from the above two piano sonatas, there are his Fantasias in D minor (K. 397) and C minor (K. 475); his Piano concerto 20 in D minor (K. 466, 1785) his ‘G minor’ Symphonies (numbers 25 and the famous 40) and of course the Requiem in D minor (K.626).

Could it be that Mozart reserved that minor ‘mood’ for his weightier works? The great contemporary Austrian pianist Alfred Brendel said that “the minor confronts you in Mozart as the superior force”.

Mozart was aged 22, visiting Paris in 1778 when his mother passed away. His K. 310 sonata, written shortly after, is not mentioned in his letters, but we know he was grief-stricken. In a letter to his father Leopold, informing him of the sad news, he wrote: “I have indeed suffered and wept enough – but what did it avail?”

It is hard not to imagine that the tragic loss finds expression in this dramatic, dark composition.

As any experienced musician will testify, Mozart’s music is fiendishly difficult to play well even when seemingly innocuous. There is just nowhere to hide, the texture is so transparent.

Emperor Joseph II (in)famously told the composer his composition had “too many notes”; this sonata has some bravura ‘moto perpetuo’ passages too. There are moments of uneasy tension, conflict and dissonance.

In the development section of the first movement, the right hand is called upon to play three ‘voices’ simultaneously. (Interestingly, this same movement has been transcribed for three classical guitars, performed by Trio Elogio on YouTube).

The second movement, Andante cantabile con espressione, in a consoling F major, offers a respite, but the final movement, again in A minor, gives a few glimpses of hope before rushing to its conclusion in bleakness and despair, presaging the music of later composers such as Beethoven and even Chopin.

I have been hearing about the musical phenomenon that is Ayaan Deshpande ever since he burst like a meteor on Mumbai’s musical horizon in 2021. But I only heard him play live in February this year, quite by chance.

I had gone backstage at the Jamshed Bhabha theatre after the opening concert of the Spring 2024 concert season of the SOI which had featured Barry Douglas playing Brahms’ First Piano Concerto. Suddenly there was a stir; a visiting influential musician wished to hear Ayaan. It was an extempore request. Ayaan had come to attend the SOI concert, and now he was being asked to perform himself!

A small crowd gathered backstage around the Steinway concert grand piano as Ayaan began to play, from memory, divinely, Claude Debussy’s ‘La plus que lente’. Sitting on the edge of the piano bench so that his feet could work the pedals, he cast a spell that made all of us forget the lateness of the hour or anything else.

After he had finished someone wondered in a whisper, “Where does such a gift come from?” I think the answer is obvious. Listen to Ayaan play and to me that is proof that there is a God.

Come here him yourself. It will be an evening you will tell your grandchildren about: “I was present at Ayaan Deshpande’s Goa debut when he was just ten years old.” This boy is destined for great things.

(An edited version of this article was published on 21 April 2024 in my weekend column ‘On the Upbeat’ in the Panorama section of the Navhind Times Goa India)